The symbol @ is so commonly used today that most of us don’t even notice it. I’ve heard it being referred to as “at the rate of” and I didn’t think that that was its actual name. Which got me wondering on what its real name was, and how did it end up in our email addresses.

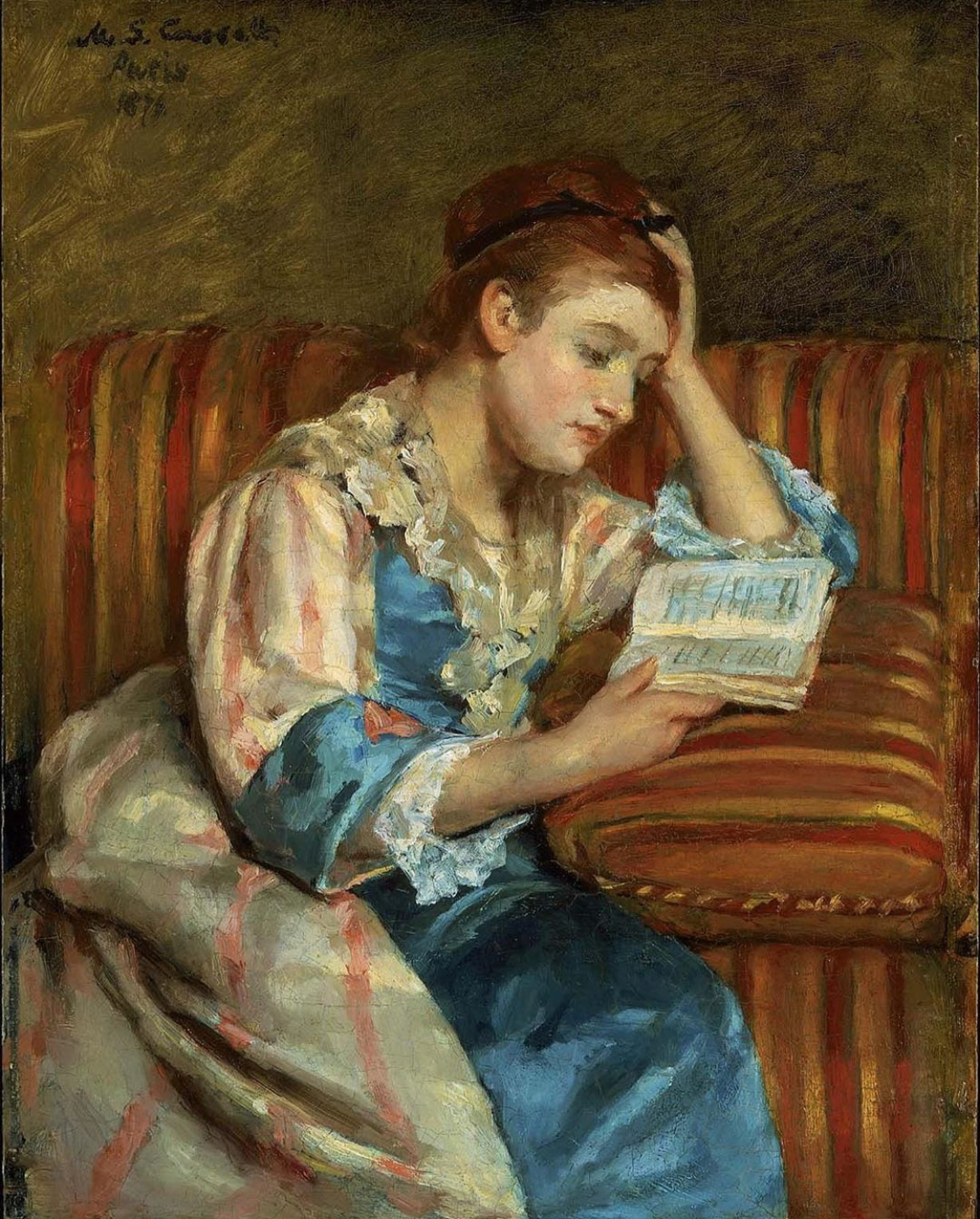

The origin of the symbol again goes back to the ingenious medieval scribes looking to make their job of scribing easier by finding shortcuts. They may have used the symbol for the Latin word “ad” which means toward. It’s first known use though is where it was used to represent the words “each at” and the e and a being joined together to form the symbol.

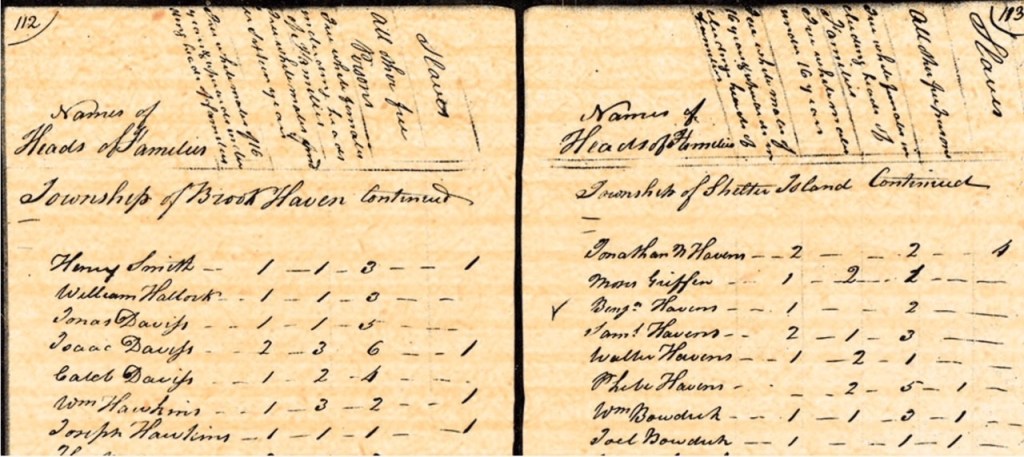

Its first documented use, from where it also gets its name, was in 1536 when a Florentine wine merchant Francesco Lapi used the symbol @ for units of wine sold in clay jars or Amphoras. With this its use in commerce started and merchants started to use it to tell the price of each unit of the item being purchased – 10 loaves of bread @ $1, meaning total cost of $10. Its use in this manner in commerce continued until 1971, and perhaps it was this exclusive use in commerce that made it a good option for use in emails.

The typewriters of 1800s did not even include the symbol in their keyboards. It was not until 1971, when computer scientist Ray Tomlinson was looking for a way to start sending emails outside of his host environment, and into another host environment that he noticed the barely used @ key on the keyboard of his computer. He realized it was barely used which made it easier for him to choose it. He used it to separate his name from the host network name – and changed the history of the barely used Amphora.

With this decision, the @ symbol was rescued from obscurity, and a life in history books. By using it as the bridge between individual and host network names, he made it the most important part of how humans connect and interact with each other in the digital world.