I believe our sorrow can make us a better country. I believe our righteous anger can be transformed into more justice and more peace. Barack Obama. 2016.

I believe our sorrow can make us a better country. I believe our righteous anger can be transformed into more justice and more peace. Barack Obama. 2016.

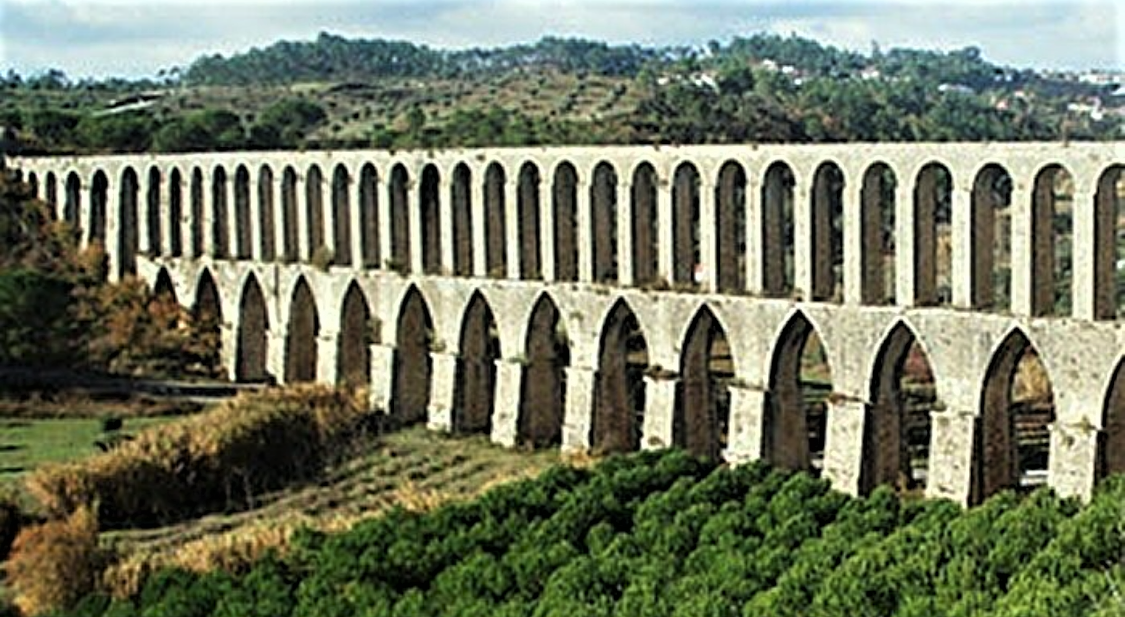

Of all the things the Ancient Romans did, what fascinates me the most are the Roman Aqueducts. These bridge-like structures supported by multiple levels of Roman arches can be seen spanning across valleys in many countries across Europe and North Africa – territories that were part of the Roman Empire. The aqueducts carried fresh water into Rome’s homes, baths, and fountains. In fact, even today the famous Trevi fountain in Rome is fed by water from an aqueduct that was built in 19 BCE.

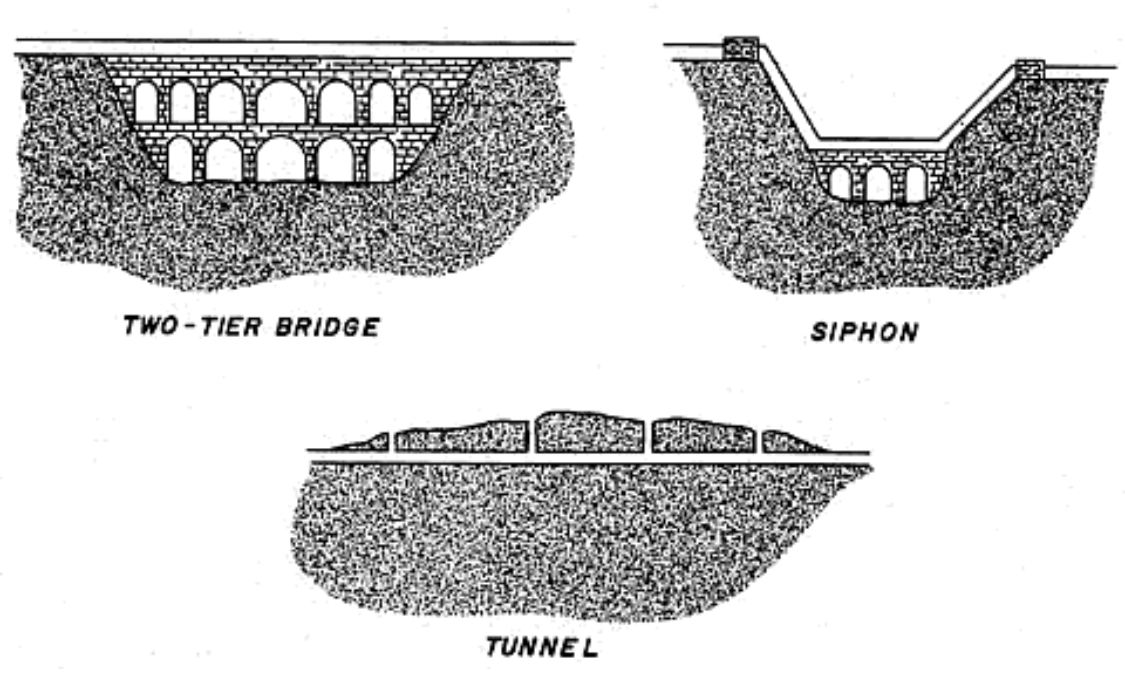

The Romans built the aqueducts from 312 BCE to 226 CE, under the rules of Augustus, Caligula, and Trajan. While the parts above ground are the most recognizable, a majority of the aqueducts were laid below ground – and are made up of underground tunnels, pipes, and canals. Of a total of 420 kms of aqueducts, only 50 kms are above ground.

The water flowed from dams, reservoirs, and other sources towards Rome because of gravity. The entire aqueduct system had to have just the right gradient – too much and the water would flow too fast particularly into Rome and burst the pipes, too low and the water would stop flowing. The Romans used rivers and riverbeds to learn about gradient technology to allow water to flow at the correct speed. The engineering knowledge the ancient Romans must have possessed to achieve this feat is remarkable.

Once the water arrived in Rome, it went into a large storage reservoir called the main castellum. From the castellum, the water traveled to different parts of Rome in smaller channels, and entered a secondary castellum, from where it further branched until it reached its final destination like the Trevi fountain.

The ancient Romans built 11 aqueducts in all. Some of the Roman aqueducts are Aqua Claudia, Aqua Appia (oldest), Aqua Anio Vetus, Aqua Marcia (could take water up to Palatine hill), Aqua Alexandina (last one built), and Aqua Traiana.

It almost sounds like I’m going to write about the movie director Quentin Tarantino – but I’m not – not that it’s not the most fascinating name – but I’m actually writing about something that’s been on everyone’s mind a lot lately – Quarantine.

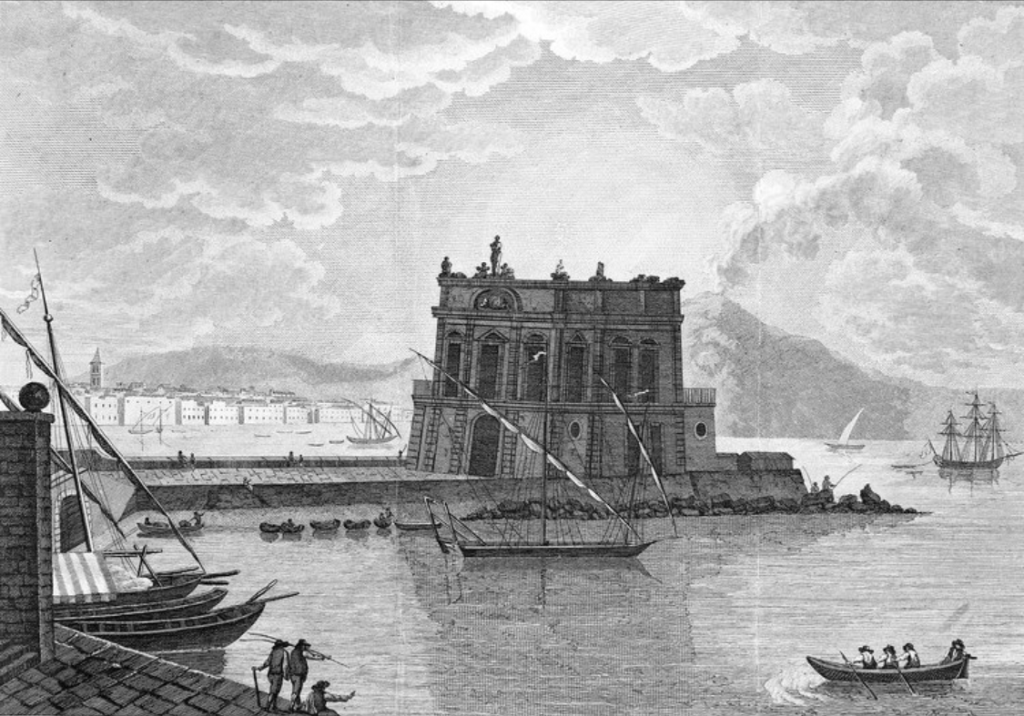

Quarantine comes from the Italian word Quarantino, which comes from the Latin word quaranta giorni – which translates to “space of forty days.” The policy of quarantine was first enforced during the bubonic plague in 1348 in Venice. Ships carrying sailors and cargo had to stay on the ship in Venetian lagoons for 40 days before they could enter Venice.

Even before the Venetian quarantine the city of Dubrovnik in Croatia became the first to pass laws requiring a mandatory order for all inbound ships and sailors to stay away from the city for a period of 30 days for fear of carrying infection into the city. The sailors were sent to an uninhabited rock island for 30 days – and this was called trentino. This is the first known evidence of isolation and is remarkable that the officials of Dubrovnik had this much understanding of diseases and incubation.

The 30 days was later changed by Italians to 40 days – and this makes us question – why 40 days? The period of 40 days has numerous biblical references – and may have been picked for that reason. According to the bible when God flooded the earth it rained for 40 days and 40 nights, and Jesus fasted in the wilderness for 40 days. Even today, in many countries, women have to rest for 40 days after childbirth.

Another interesting and related term is Lazaretto – which is the place where the quarantine took place, or a place where people with diseases, especially lepers, stayed. The term traces its origin to the biblical Lazarus who was covered in sores. So for instance the rocky island near Dubrovnik where the quarantined (or should I say trentined) people were sent would be a lazaretto.

This is how Prime Minister Winston Churchill announced the end of World War II 75 years ago today. On May 8, 1945, after six years at war in which millions of young lives were lost, the guns finally fell silent over Europe. The Allies defeated Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany, and the day became known as VE – Victory in Europe – day.

75 years later the generation that fought this war remains undoubtedly the greatest generation. The sacrifices made by the young men and women of this generation defy understanding, and we owe them an unpayable debt of gratitude for the freedoms we all take for granted. The men that fought this war, those that are still alive, continue to inspire and amaze us to this day. One such hero is World War II veteran captain Tom Moore who turned 100 years old on April 30th.

War veterans like Captain Tom know how to inspire – they have seen the worst of humanity, they have lived to tell about it, they choose to see the positive instead of dwelling on the negative. Captain Tom has singlehandedly brought the UK – perhaps even the world – together at this time – across generations and across all financial and racial boundaries. Captain Tom, a lifelong fan of Britain’s Health system (NHS) decided to walk a 100 laps of his garden by his 100th birthday to raise $1200 for the NHS.

A world dealing with a pandemic found its hero – and Captain Tom raised $40 million. He received 125,000 cards on his birthday, a Royal Air Force flypast, and a possible knighthood. And like all people of his generation, Captain Tom told the world to remain positive and hopeful: “For all those finding it difficult: the sun will shine on you again and the clouds will go away.” What an amazing man!!

As the world battles with an enemy of a different sort, on this day when six years of darkness ended, we should pause and remember the heroes of World War II that sacrificed so much, and learn to live life with the same grace that they showed during and after the war, and continue to show to this day.

There’s Mayday and there’s May Day – the 1st day of the month of May which falls right in between spring equinox and the summer solstice.

Mayday, Mayday, Mayday !!– interestingly has nothing to do with the lovely month of May. It’s the international signal for a distress call over the radio – and it has to be used only when the distress is real, life-threateningly real. And it has to be said three times so there is no confusion over static radio signals as to what the caller is saying.

Mayday as a distress signal started in 1923, when a radio officer at the Croydon Airport in London came up with this term – primarily because it sounded like the French word for help me m’aider. Also it had no ‘s’ or other sounds which tend to get lost over radio signals. For non-life-threatening issues the signal is pan-pan pan-pan pan-pan which is a derivation of another French word “penne,’ which means breakdown.

May Day on the other hand is a word that relates to this day which traditionally is celebrated with May flowers in baskets and dancing around maypoles. All across Europe, the seeds sown in springtime had started to sprout and this was cause for celebration – cattle were driven to pasture, special bonfires were lit, and people decorated their front doors and filled baskets with May flowers. Many of these festivities were shunned by the Puritans, and traditional May Day celebrations never really took hold in the US.

Starting with the 19th Century May Day took on a new significance – it became the International Workers’ Day – a day that celebrates the struggles and gains made by the labor movement such as the fight for an 8 hour work day in the US. May 1 was chosen as Workers’ Rights Day in 1889 as an homage to the May 4, 1886 Haymarket Riots in Chicago. The communist states embraced this day and used it unite workers against capitalism. It became famous for the spectacular annual May Day parade in the Red Square in Moscow. After the decline of communism, the importance of this day diminished in the communist countries.

(Images courtesy Old Farmer’s Almanac).

The journey of the hashtag is long and storied – it saw many lives before it became the powerful organizer of tweets by topic. Like many of the other symbols, its first known use too was by the Romans.

Its origins started with the Roman use of the short form “lb” for libra pondo or “pound in weight.” Eventually, with its use in English, and as people started writing faster, a line was placed across the lb until it started to look like #.

The # was included as a character in printers, though it continued to be called pound sign. And then in the 1870s it reached the typewriter (often on the 3 key).

The # symbol saw another life as an octothorpe when it got included on the telephone keypad. It was this inclusion on the phone keypad that made it a well-known symbol to the general public. The # on the phone started to signify numbers in automated customer service systems, and it would have stayed like that forever, had it not been for Chris Messina’s attempt to organize Twitter.

Looking for a way to organize twitter by topicality, Chris Messina chanced upon the # symbol, and used it for the first time in a tweet on August 23, 2007, “how do you feel about using # (pound) for groups. As in #barcamp [msg]?”

Chris Messina used the # symbol as an organizing tool for the Twitter community. Twitter did not have a way to support groups, and using the # symbol provided a way to categorize by topic, and indicate topicality. He only picked it because it already existed on mobile phone keypads, and was therefore readily available to use.

And with that, a symbol that started its journey with the Romans finally achieved greatness in social media as a hashtag. On a daily basis around 125 million hashtags are shared daily on Twitter.

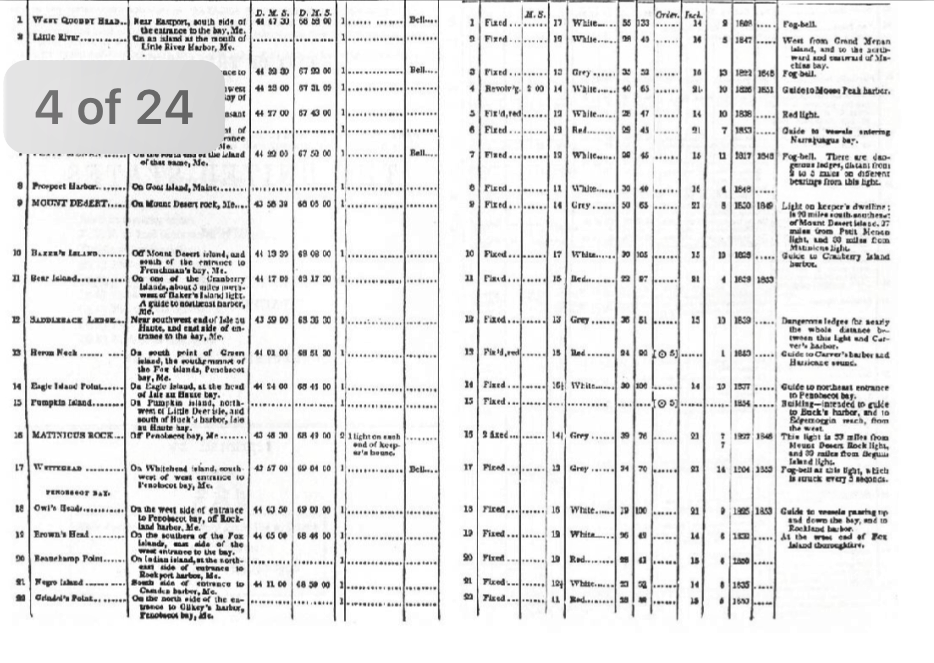

For centuries, lighthouses have been the guiding light that have helped weary travelers find the way home. Standing steadfast at the edge of turbulent waters, these lighthouses have been a beacon of hope since ancient times. The US coastline is dotted with more than 1000 lighthouses – starting with the Boston Light in 1716, which still sits on a rocky island 10 miles out in the Boston Harbor.

These lighthouses were instrumental in building the nation – the colonies built lighthouses along the coast to make navigating their shores safer for maritime sailors. They also played an important role during the Revolutionary Wars, as a result of which in 1789, The First Federal Congress passed the Lighthouse Act which was the nation’s first public works program. The US Lighthouse Board, established in 1847, was the second agency of the US Federal Government. The list below shows lighthouses from Maine to Michigan.

These lighthouses became the guiding light which guided the settlers to new lands across the vast expanse of this nation’s coastlines and lake shores.

The oldest working lighthouse in the world is the Hook Lighthouse which was built around 1210. It was built by the monks who had lived in a monastery there since the 5th century, and had a practice of lighting a warning beacon at Hook Head. This tradition of warning sailors and fishermen continued for centuries until a lighthouse was built around 1210.

The 1868 Lighthouse Board Report included this statement, “Nothing indicates the liberality, prosperity or intelligence of a nation more clearly than the facilities which it affords for the safe approach of the mariner to its shores.” With these lighthouses that dotted the coastline, the United States has always kept the light on at night, making sure its people find their way home safely.

The symbol @ is so commonly used today that most of us don’t even notice it. I’ve heard it being referred to as “at the rate of” and I didn’t think that that was its actual name. Which got me wondering on what its real name was, and how did it end up in our email addresses.

The origin of the symbol again goes back to the ingenious medieval scribes looking to make their job of scribing easier by finding shortcuts. They may have used the symbol for the Latin word “ad” which means toward. It’s first known use though is where it was used to represent the words “each at” and the e and a being joined together to form the symbol.

Its first documented use, from where it also gets its name, was in 1536 when a Florentine wine merchant Francesco Lapi used the symbol @ for units of wine sold in clay jars or Amphoras. With this its use in commerce started and merchants started to use it to tell the price of each unit of the item being purchased – 10 loaves of bread @ $1, meaning total cost of $10. Its use in this manner in commerce continued until 1971, and perhaps it was this exclusive use in commerce that made it a good option for use in emails.

The typewriters of 1800s did not even include the symbol in their keyboards. It was not until 1971, when computer scientist Ray Tomlinson was looking for a way to start sending emails outside of his host environment, and into another host environment that he noticed the barely used @ key on the keyboard of his computer. He realized it was barely used which made it easier for him to choose it. He used it to separate his name from the host network name – and changed the history of the barely used Amphora.

With this decision, the @ symbol was rescued from obscurity, and a life in history books. By using it as the bridge between individual and host network names, he made it the most important part of how humans connect and interact with each other in the digital world.

One of the most amazing things about the world is how small and interconnected it is and always has been. When we think of the ancient world, the civilizations seem distant and completely removed from each other – and yet somehow people traveled across continents, connected with each other, fought wars, and forever influenced or changed each other. And in this process of connecting with each other, they left a richer world for us to inherit.

Nowhere is this global connectivity more evident than in the Rosetta Stone. This slab of black granite with writing on it shows us the connections we have with each other – Alexander from Greece invades ancient Egypt and his General’s descendants become the Ptolemy rulers of Egypt. Much to the dislike of the Egyptian high priests and natives, they only read and write in Greek. The high priests write in Egyptian hieroglyphics, whereas native Egyptians write only Demotic. So all legal papers, or granite slabs as the case may be, have to be written in all three languages – particularly one in which a descendant of Greeks is staking his claim on the throne of Egypt.

The slab gets moved around in Egypt first by the pharaohs and later the Turkish Ottomans, until over 1500 years later it is found in an Egyptian town called Rosetta by a Frenchman from Napoleon’s army – only to be taken from them by the British army under the Treaty of Alexandria. And now, another 200 years later the Egyptian museum would like Britain to return it to them.

It is these connections we have with each other that allowed humanity to gain insight into the greatest civilization the world has ever seen. The world becomes richer when we learn from our ancestors – and the deciphering of hieroglyphics through the Rosetta Stone gave us this knowledge and insight into the lives of ancient Egyptians.

On the surface, it’s an ancient stone monument, a decree by a King written in three languages. But to only see that in the Rosetta Stone is to not see it at all. Its power lies in what it represents, and its ability to remind us of the human need, since ancient times, to connect with each other across boundaries, to roam the wide expanse of this earth, and to understand our world and the people that inhabit it. (This vignette was written by my sister during her study abroad in London, after a trip to the British Museum. All photographs courtesy of British Museum)

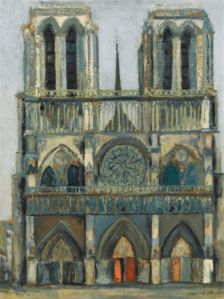

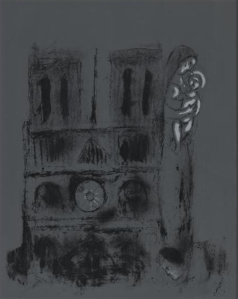

On this Easter Sunday I started thinking of the magnificent Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris, which had a devastating fire almost a year ago. On Good Friday this year the cathedral had a small closed service. Regardless of one’s faith, the beginning of the rebirth of this medieval church from the ashes of that devastating fire, is reason enough to celebrate.